As I get further along the path of making things for my home, I've found that the things that aren't made by me, and especially the ones that are made of ugly plastic or are otherwise crappy, beg to be dealt with. Specifically, they beg to be replaced by something hand made, or at least by some natural material.

planning with sketches

There's also the perpetual discussion among woodworkers about dealing with all the scrap wood and cutoffs that woodworking creates. On one side, there are the fanatical, I'm-thriftier-than-thou zealots who loudly proclaim "Scrap wood?!?! There's no such thing!", and go on to explain how they went from using the 200 year old trees on their property to build their house, then all furniture in it, then scores of picture frames and cutting boards, then turned a bunch of pens, and now pick their teeth with the remainder. On the other side, there are the "I only have what I need for my current project" types, with the rest heading right into the "burn pile" (those people usually have wood burning stoves), or even the trash. Most of us woodworkers are somewhere in between, and deal with the scrap wood problem like most people (and us too) deal with being overweight: we do our best, we could do better, and we're always just a little big heavier than we want to be.

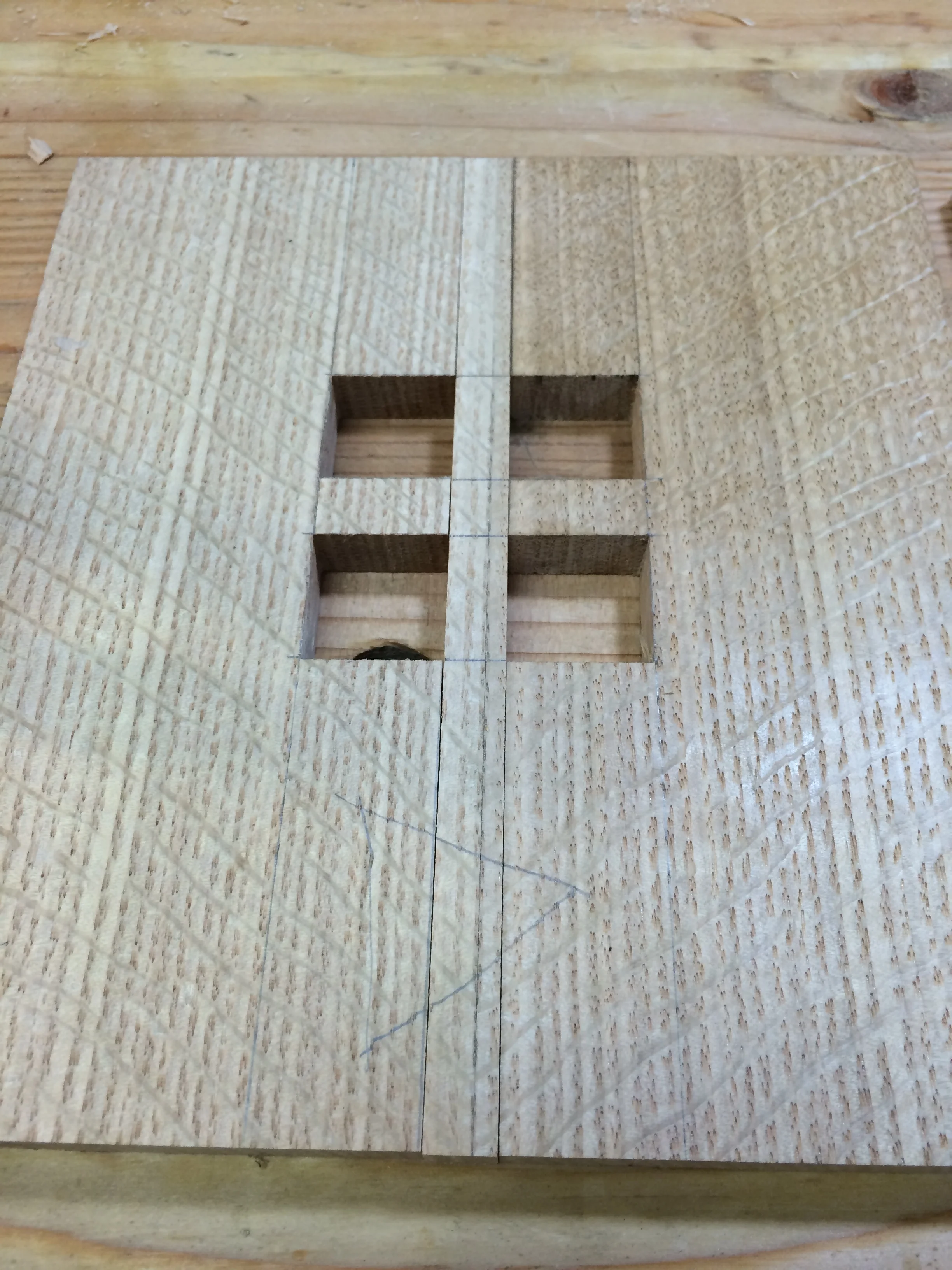

the "leaves" design

My own scrap wood coping technique is to have both a large lumber cart, for sheet and large flat things, a small cart for long & narrow things, and several lumber shelves for the very long boards. When those are full, the rest goes into my burn pile. Yup, that's the RULE. I try to be strict, I really do. But, when a cutoff is just so damn gorgeous, or when the sting of the cost of the lumber is still fairly fresh in my mind, it is hard to follow the RULE. Sometimes I'll swap out the new, better scraps for older, less useful scraps. And then, sometimes, you just get a good pile of too-good-to-toss stuff built up.

That was me a while ago with some red & white oak. Too good to toss, and it was overflowing my system. Around that time, I happened upon an image online of a great craftsman style wastepaper basket. As I looked at it, peaking around the corner of my desk, just in the corner of my eye, was an ugly grey plastic Office Depot garbage can that sits in my office, and another one around the corner in my kitchen...

So, it all clicked. Ugly stuff + some great un-tossable scrap = project, and I made these four wastepaper baskets - they're much too nice to be called "garbage cans".

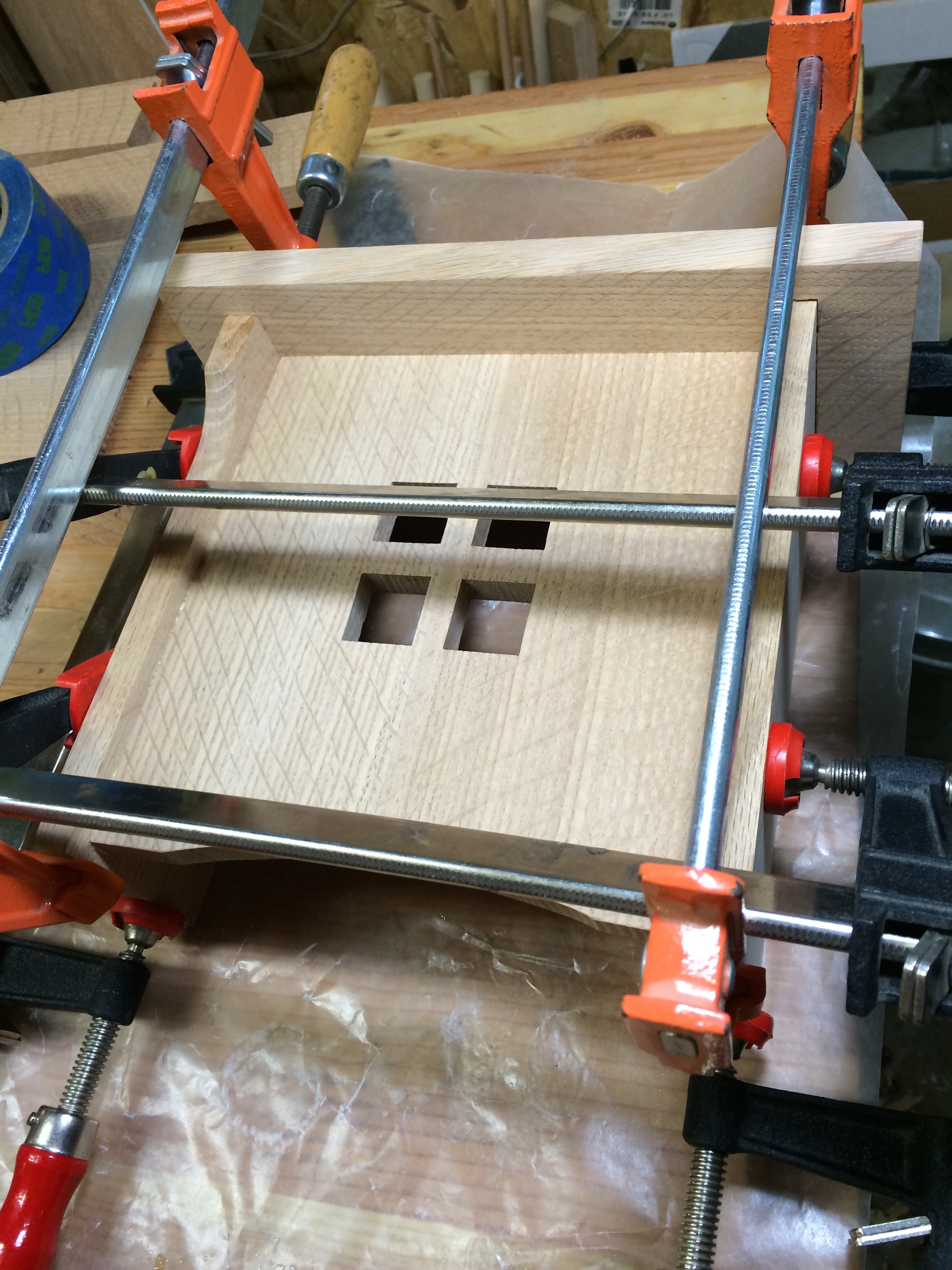

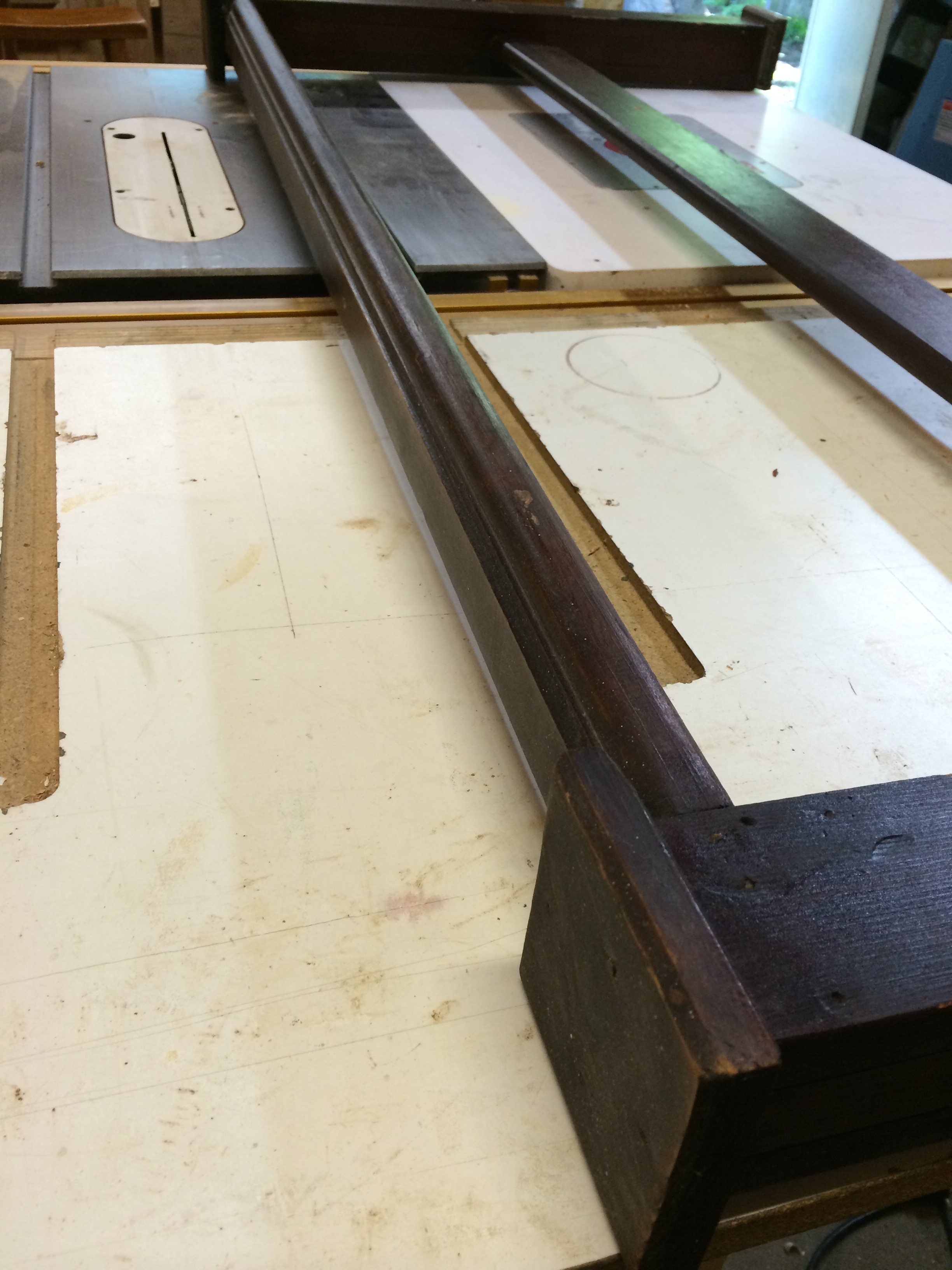

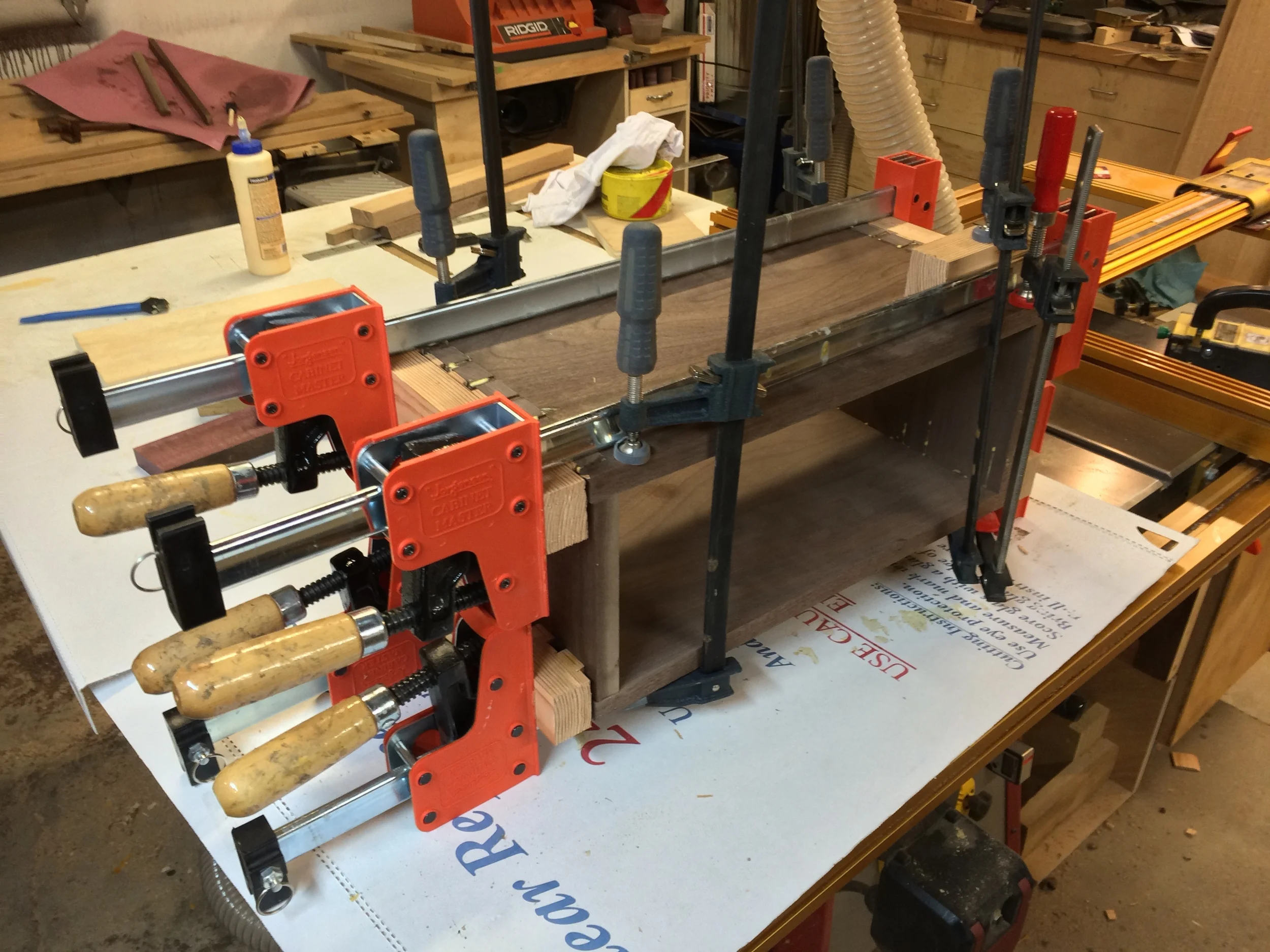

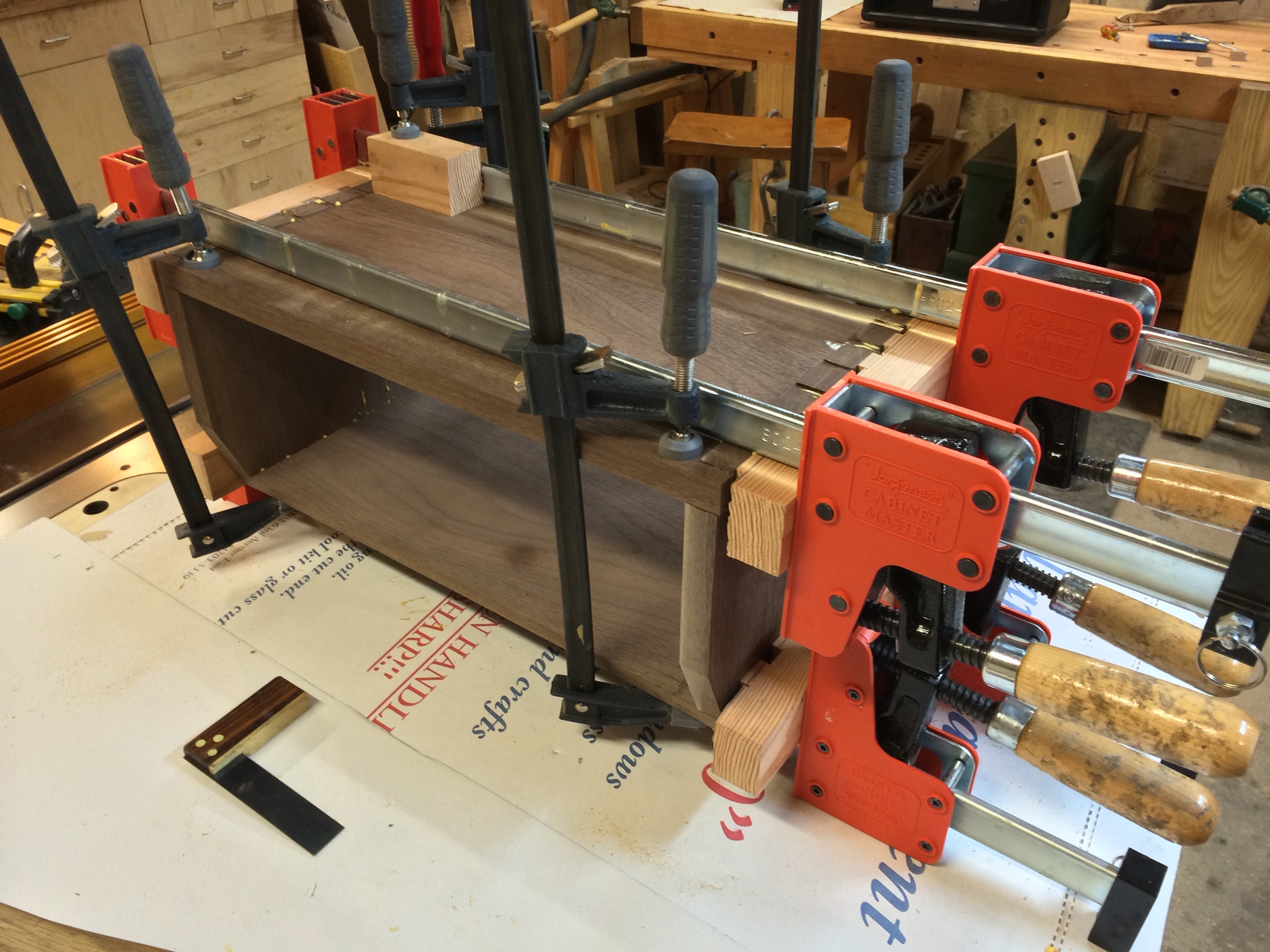

sizing and dry fitting

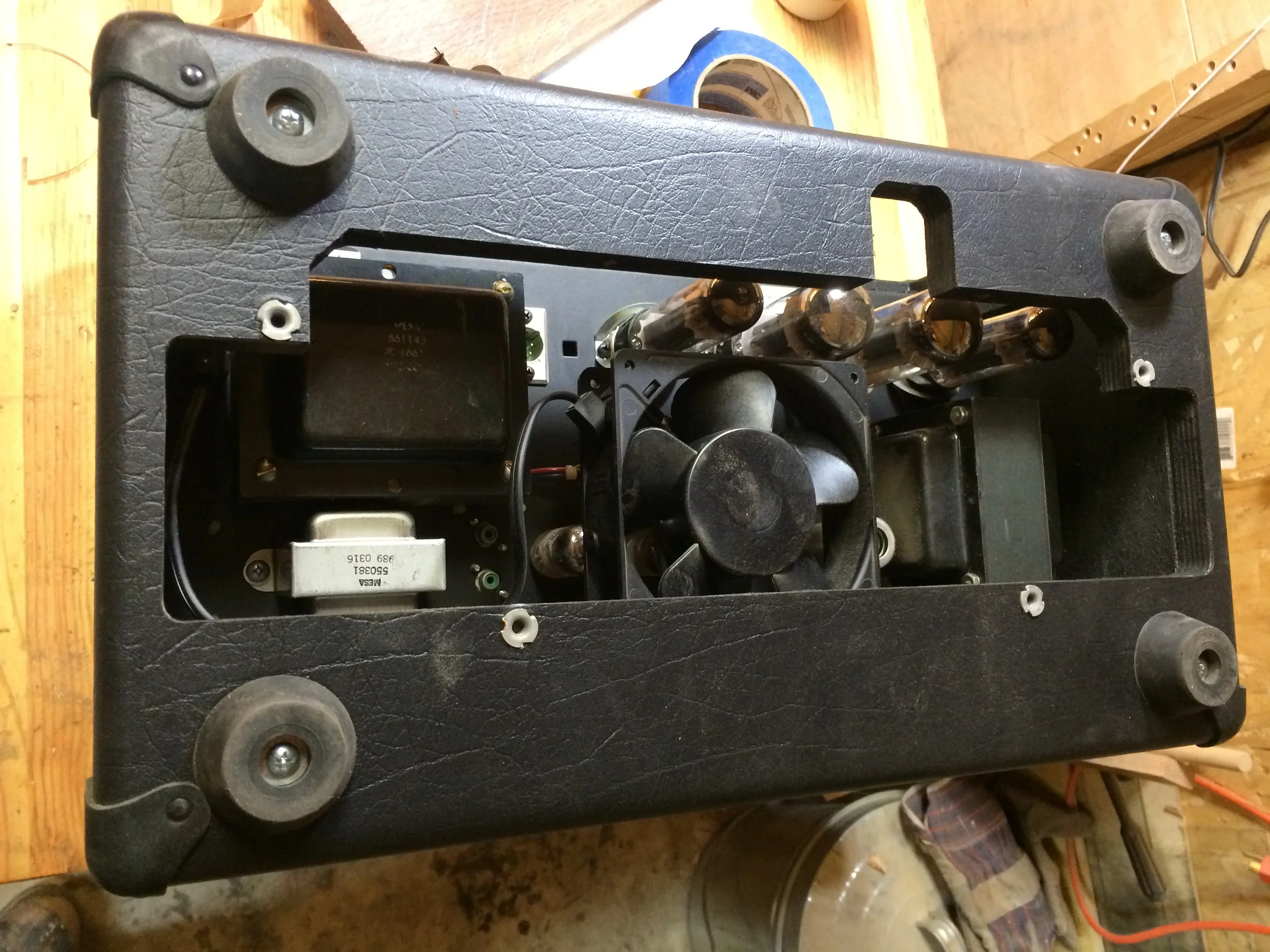

I tried three different main designs, variations on ones I saw online, and two variations of the "leaves" design. On the "leaves" design, I got a chance to try working with some different materials; brass clips on one, and leather loops fastened with copper rivets on the other. I think the brass clips idea was good, but I couldn't get a clean bend on them, and the way they look on the back isn't very satisfying. The leather loops idea came out much better, and were easier to do as well.

After the build, and with much pleasure, I relegated the plastic garbage cans to the basement, and placed the four news ones throughout the house. The brass clip version of the "leaves" one is in my office, where I don't mind the flaws very much. The only thing I might add to these, especially to the large "slats" one, is a copper liner, so that a) messier things could be put in it, and b) one would only have to empty the liner, rather than picking up the whole thing. I'd like to try making the liner with folded sheets of copper (copper roof flashing?) and a soldered weld. I've never done that before, but I look forward to figuring that out.