Working on a large project, like my current wardrobe project, takes a lot of time. And large projects go faster when I can get large blocks of time to work on them (so, that's weekends). When I have only an hour or so here & there, I find it hard to "get into" a large project, knowing that I'll soon have to stop.

Instead, I often use that time for little detours like cleaning the shop, organizing stuff, sharpening, tool maintenance, or even little side projects. And even though I'm not making progress on anything big, I'm still having fun in my shop. Here's a few detours that I went on recently.

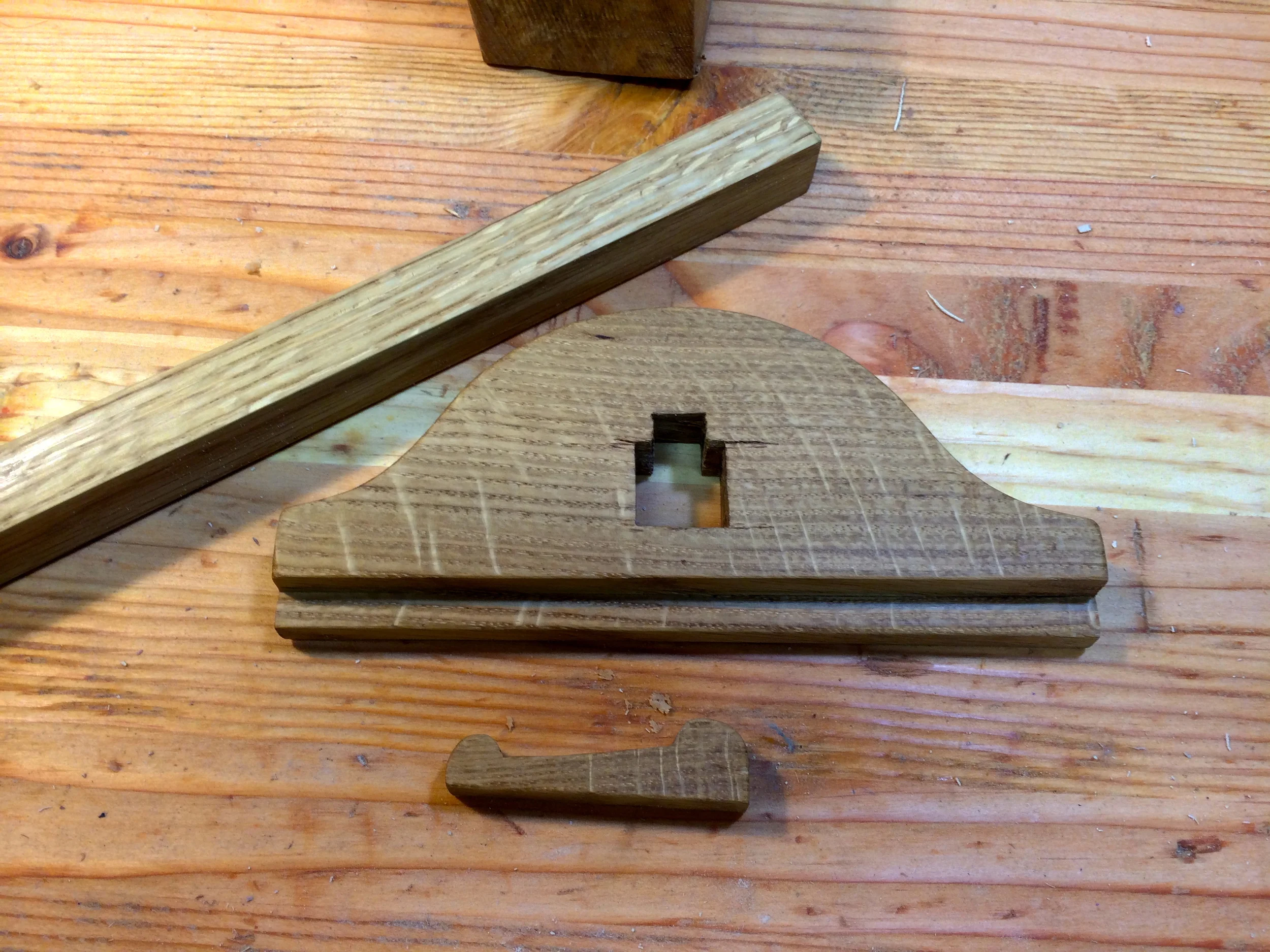

Saw Support

I cleverly (not) built myself only ONE saw bench a while ago. I works great, but when working on a long board, I have nothing to support the other end with - there's nothing around that is the right height. But I don't actually need a whole second saw bench, so instead, I but one of these saw support/work support/work stand things. It has two "levels"; one the height of my saw bench, and the other the height of my work bench. I used some scrap red & white oak for material, and mortise & through tenons to join it, with wedges for the bottom through tenons. I finished it with boiled linseed oil. It's already proven handy.

Moving Fillister Plane

I tossed a bid into an eBay auction a few weeks ago, and happened to win it. It's a cool old wooden moving fillister plane. It's nothing fancy, but it's in good shape, except for the missing nicker iron. I took a little time to knock off the rust, clean it up, and sharpen the iron. It works great. A future detour will be to find some tool steel for the iron, cut & shape it, and then harden & temper it (something I haven't tried yet, but am inspired to do so by blacksmith Peter Ross).

Band Saw Maintenance

When my band saw blade started drifting, on even the simplest cut, I knew something was screwy. Especially since I'd recently put on a new Woodslicer blade about three weeks ago. A little investigation later, and damn it if the bottom thrust bearing hadn't seized up. Amazing how that makes such a difference -- you'd think the blade could still just slide along it. Oh well, a phone call to Grizzly.com service, and in a few minutes I had the part on order. But that means no band sawing for a while.